An Island Summer

The Moon Cusser Coffee House

and Folk Music Center

By David H. Lyman. © Copyright 2022.

Something happened on the Vineyard that summer of 1963. It would change people's lives. I was there and watched it happen. You could say I was the one who made it happen, so therein lies the story I'm about to tell.

In the summer of 1963, the Vietnam War was in full swing. Kennedy was in the White House. The Beatles were not to arrive until later that fall. Woodstock was still five years away, but folk music was still folk music and as popular as rock-and-roll, even more so than the blues and most forms of jazz. In Boston, coffee houses and folk music were the rage. It's a college town, with a quarter of a million underage college students looking for somewhere to go on the weekends. Coffee houses, served up music but no alcohol. The perfect place.

The Unicorn, on Boylston Street, was the largest of the folk clubs in the Boston area. It was in a basement, down two flights of stairs, under a furniture store. Today, there’s an Apple Store above. It would seat or stand about 100. The Club 47, just off Harvard Square in Cambridge, was slightly more "authentic,” better known but smaller, with more traditional performers. The Cafe Yana, next to Fenway Park, was the smallest and featured local acts. Jackie Washington played at The Green Parrot on Kenmore Square. The Kings Rook up in Marblehead was more of a real coffee house than a folk club. There were others, most short-lived.

I was drawn to folk music in high school, mostly for the stories the music told. I tried to play the banjo but failed. I gravitated to the tape recorder, which led to a ten-year career in radio, first as an engineer (while still in high school) and then as producer and host of a weekly folk music show in Boston on WBUR, while a broadcast journalism major at BU.

Before graduating, I’d run out of money and patience with academics, and dropped out. Besides, I was already working in the field I was studying. In this "creative world," no one asks what college you went to; they want to see your portfolio and what "experience" you've had. By now, I had a Saturday evening folk music radio show on WBCN; and a day job as a floor producer at Channel 5, WHDH-TV. This gig included a role as the Ring Master on the Bozo afternoon kids’ show. In the evenings, I managed the Unicorn Coffee House. It was owned by a crazy Egyptian-Greek, George Padapolo. George could care less about the music, but he knew a profitable scene when he saw one. He hired me for my passion and knowledge of music, and was off organizing a film festival and a jazz club. I had a free hand.

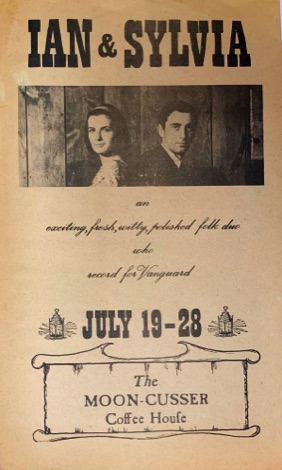

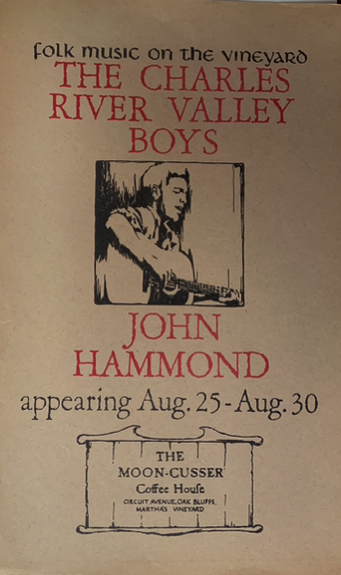

The club had two acts each night: a local performer like Tom Rush, Ben and Bobbise, Ken Lens, and the Charles River Valley Boys. Then I got to bring in performers I liked: The Clancy Brothers, Ian and Sylvia, the Limeliters, It was magic. People came for the music. There was no booze, just five kinds of coffee or tea. The cover charge was $2. Between acts, there was time for what coffee houses were invented for: conversation.

Ginny Blackmar and a trio of females from Colby Junior College in Wellesley would show up Friday evenings. If they didn’t make it back for curfew, they stayed in town and were there on Saturday nights as well. As I was making the rounds of the tables one evening, I stopped at Ginny’s table and got into a conversation. Her family summered on Martha’s Vineyard, she told me, and the Vineyard would be a great place for a folk music coffee house in the summer. The idea stayed with me for weeks. A summer on The Vineyard—it would be better than staying in Boston.

I was reluctant to share the idea with George, the Unicorn’s owner. He’d take over. I’d be just a hired hand. I wanted this to be “my place” with my ideas for what a folk club should look like.

Quietly, I began talking up the idea at the club. Two of the regulars, Fritz Dvořák and Dick Randelet, both electronic engineers from Route 128, were interested. I drew up a budget to show them what I felt we’d need: how much for rent, staff, the performers, equipment, and what we could expect for income. They became more interested in the idea than in the profit I projected. They pooled their resources and backed me with $2,000 each. Dick and I visited the Island in April, where we found a recently vacated grocery store on Circuit Avenue in Oak Bluffs. The space was huge. It would seat (legally) 125. It would be perfect, and the price was right.

With a signed lease, an application for common victuals licenses, and other necessary permits filed with the Oak Bluffs’ selectmen, the work began to assemble the pieces. Over the next two months, working part time as the Ring Master on the Bozo television show, hosting my radio shows, and managing the Unicorn, I bought used equipment, cups and saucers, plates, and flatware from kitchen supply dealers, along with a PA system, theatrical lights, and a cash register. From Good Will, I purchased 20 old tables and 100 chairs. We printed menus and placed an ad in the Gazette for summer staff.

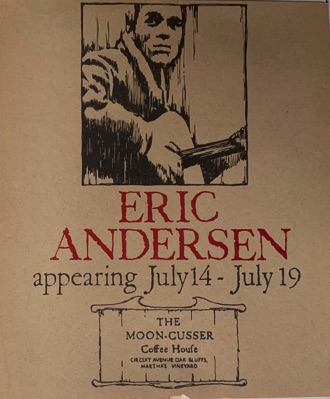

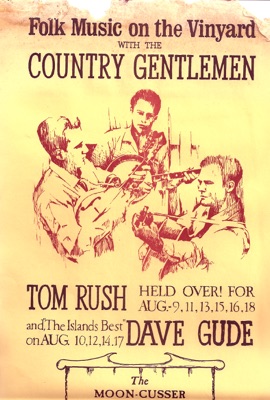

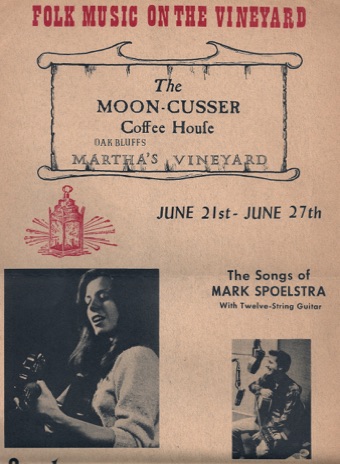

The local Boston performers I knew: Tom Rush, Jeff Muldour, and The Charles River Boys, so Mitch Greenhill, a booking agent in Boston, helped me assemble the summer’s schedule of major acts. Mitch, himself a folk musician, knew the folk scene better than I did. Some of the summer’s headliners included performers I knew from my radio shows, but Mitch added some of folk music’s most ingenious singer-songwriters and performers: Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Bud and Travis, Ian and Sylvia, The Country Gentlemen, and Bonnie Dobson. Jean Redpath.

The Moon Cusser

We needed a name and a motif. The Unicorn had an “Arthurian” theme. With a few suggestive touches George had around the walls, the patrons were able to step back into the days of Chaucer, knights, and ballads of chivalry. It doesn’t take much to get the audience to believe. But I had an old supermarket that needed a complete facelift. I wanted to create a colonial New England atmosphere with a warm, rustic barn-like interior.

We needed weathered barn boards. Randelet had found an old barn in Wellesley that needed tearing down, so I tore it down. We needed the weather boards to cover the wall, but there weren’t enough, so we would use panels of brown burlap to alternate with panels of barn board. The textures not only gave the space a warm environment, but the wood and fabric cut down on the reverb from the stage and created a softer audio tone.

We used the burlap to cover the huge glass store front to keep prying eyes from seeing inside. I built a colonial-looking sign that hung on a bracket over the front door.

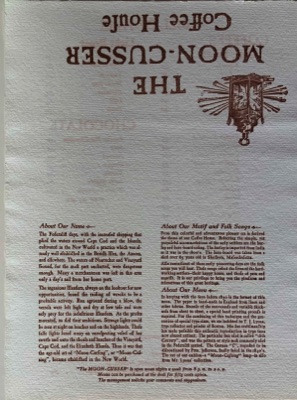

To go along with the colonial theme, I needed a name that conjured up the past and was slightly naughty. The name Moon Cusser came from New England’s shadowy past. From Samuel Elliot Morrison’s book on New England maritime history came the ”backstory” for the name.

Moon Cussers were Englanders and colonial New Englanders who lived along a coast. They were apt to hang fales lights on the cliffs on dark moonless night, to lure ships onto the beach where they plunder them. They curse the moon when their subterfuge was reviled.

\We needed menus and posters. An old printer with a letterpress shop on Commonwealth Avenue in Brighton showed me hand-made paper that looked like ancient parchment. He introduced Caslon Antique, a type face that looked like it came from the fifteenth century. “The colonists use a similar font,’ he told me. “If you want to be truthful about the colonial period you want, you’ll have to replace an “s” with an "f."

That meant “house” would now be spelled “houfe.”

You’ll need an icon, he added, something graphic that represent the brand. He showed me lots of engravings, but the one that jumped out was that of an old barn lantern. The moon cusser’s lantern.

Small details began to add up to create the illusion that was forming in my imagination.

With the summer schedule of weekly acts almost done, in May, we loaded a rental truck with the barn board siding, two large rolls of brown Indian burlap, the kitchen gear, tables, and chairs and drove to the Vineyard. With a crew of local kids, we turned the old supermarket into a cozy nightclub, one that would not serve alcohol.

There was a 2-foot-high stage against one wall and a false balcony opposite that housed the stage lights, creating a more intimate, cozy setting. A barn board barrier was installed at the entrance, directing people to the cash register to pay the $1.50 cover charge. The walls were covered in alternating panels of barn board and burlap. Tables and chairs filled the floor. Bathrooms were installed off to one end of the room, adjacent to the kitchen. A stair well led to the basement, which was turned into a made-shift “green room” for the musicians. There was a pay phone on the wall by the kitchen. Our phone number was MV #211.

The week before we opened was hectic. The place needed to be built, bathrooms installed, a stage constructed, lights rigged, posters printed and put up, ads placed in the Gazette, deals made, and staff hired. Rambling Jack Elliott’s wife, Janet, whom I’d met the previous winter in Boston, came along as my head waitress. An ad in the Gazette for an assistant manager produced Philip Metcalf, a clean-cut Princeton Junior, a Vineyard summer resident whose family belonged to the East Chop Beach Club. Philip knew the island, and he had a 1951 yellow ragtop Jeepster. It was the Jeep that got him the job. I needed a vehicle to tour the island each week, putting up posters.

Philip’s job was to stand at the cash register each evening in his blue Princeton blazer, which added a degree of respectability to an otherwise seedy operation, and collect the cover charge. He and I quickly formed a friendship, one that lasted for 60 years until his untimely death in 2019.

Things came together those last few days. It was like summer stock—24-hour days of construction, painting, setting up, and organizing. A few days before we were due to open, I appeared before the Oak Bluffs Selectmen to answer their questions about our entertainment licenses. I showed up in a sport coat and slacks, no beard, and my short hair combed. The last thing I wanted was to look like a hippy.

"No, there will be no alcohol served.”

"Yes, we will cease entertainment at 1 a.m.

"Yes, we will admit minors. That’s one of our goals. To be a place where anyone who loves music, regardless of age, can come, see, and listen to really great, world-class musicians."

We got the licenses. All the other permits were in place for the new bathrooms, the fire marshal’s inspection was completed, and seating capacity signs were posted (and mostly ignored). The local cops stopped in. There was a buzz in the air. Would this be a den of iniquity or something else? The Moon ‘Cusser actually became known as a place where parents could drop off their kids on their way to a fancy restaurant in Edgartown, then pick them up on the way home later that night. For the price of a $1.50 cover charge, a $2 desert, and a mug of non-alcohol Vineyard Grog (grape and cranberry juice and ginger ale), it was cheaper than a Nanny.

Opening Night

By opening night, Friday, June 21, 1963, all of us were exhausted, but we’d make it. “The Show Must Go On” . . . and it did. We had three acts that weekend: The Charles River Valley Boys, an old-timey band from Boston, opened with lively bluegrass. Also on the bill that week were singer-songwriter Mark Spoesltra and Texas singer-songwriter Carolyn Hester. They packed the place. It was a sell-out crowd. I was out back in the kitchen training my new staff how to make a variety of coffees. Philip was out front collecting the $1.50 cover charge and handling the stage lights.

Halfway through the first act, Philip came back to the kitchen.

“There are three rather large Irish-looking gentlemen out front who wanted in, and they say they are not going to pay cover—besides, we're full. There is not a seat in the house.

“Everyone pays..." I said that and went on slicing up an apple pie.

Philip came back a few minutes later and said, “They said they'd tear the place apart if they didn’t get in... I believe they could. They said to tell you they are the Clancy Brothers.”

"The Clancy Bothers?”

"You know them?”

"Of course I know them. We are old friends, but they are supposed to be in New York City.

"You'd better do something. Fast.”

I wiped my hands and followed Philip out front. There, in their hand-knit Irish sweaters, stood Patty, Liam, and Tommy. The Clancy Brothers

"Out of the way, Lyman, we’ve come to open this place for you.”

And open it they did. The boys had flown in unannounced, on their own dime. What a surprise! The Charles River Valley Boys had finished their first set when I climbed on stage to make an announcement.

"Ladies and gentlemen, Just in from Ireland and New York to help us celebrate the Opening of the Moon ‘Cusser . . . . the Clancy Brothers, Tommy, Patty, and Liam.” That was all I had time to say. The Clancy boys pushed me aside and took over. They sang rousing Irish drinking songs, told stories, got people singing along, and introduced Carolyn and Mark. It was a whale of an evening.

The Folk House

I’d rented a house on East Chop for myself and staff and to house the visiting musicians. It came to be known as the Folk House. As soon as the club closed a little after 1 AM, the crew and performers made a beeline for the house. I’d been the stage manager at a summer stock theater in high school; the stage manager at the Springfield Symphony my freshman year in engineering college; and spent two winters managing the Unicorn. Working with actors and musicians taught me the necessity of there being a place where the artists could relax, unwind, and keep playing after the club closed. Those late nights, after the show, was where some of the best music was created. A musician is just warming up on stage, doing what they know. Later at night, surrounded by other musicians and an adoring entourage, musicians can experiment, make mistakes, work out riffs, develop a new sound, try out lyrics, and get feedback from their peers. Can’t do that on stage. Being a part of this was magical.

That first night, after the show, the Clancy Brothers were holding fort in the kitchen; Mark, Tom Rush, and Andy Rooney from the Charles River Valley Boys and others were in the living room with guitars; the banjo pickers were on the front porch; and there was music everywhere. I was dead tired and fell asleep in the large first-floor bedroom. Around 4 a.m., a female voice whispered:

"Move over, David.” Was I dreaming? No, this was real. “I’m worn out," said the woman’s soft voice. “I can’t deal with what’s going on out here. I need to sleep."

“Sure, come on in..."

“No, you stay under the sheets,” she said. “I’ll sleep here on top, under the blanket." That was the night I slept with Carolyn Hester.

Most evenings, things didn’t get heated up until way after mid-night, but this is where people like Tm Rush, Jeff Muldour, Don Maclean, and Alan Arkin got to swap guitar styles with Charley Duffy from the Country Gentlemen. Music became the reason and driving force behind the Moon Cusser’s existence. For a few of the hangers-on, it was more “the scene,” the grass, and the sex that interested them. For me, it was the realization that I could create magic, like the peddler behind the curtain in The Wizard of Oz. With a bit of barn board and burlap, a spot light, and a sound system, with good musicians telling stories with their songs, I could transport an entire audience to Scotland, to the hills of West Virginia, back into the time of Jack the Highwayman.

How The Magic is Created

I’d learned how to create that magic while working in summer stock as a high school kid. It’s called “The Willing Suspension of Disbelief.” When an audience enters a theater, knowing, at least intellectually, they are going to see a play, a concert, or a performance on stage. It’s all make-believe. They know that. Nothing they see or hear will be real, yet they go willingly, even paying great sums of money to be fooled. Why? People want access to a life outside of their own, to experience emotions they fear in their daily lives. They want to be entertained, enthralled, enlightened, transported, made to laugh, and even made to cry. That’s the role of the writer, the performer, the storyteller, the actor, the director, and the film crew—to create an illusion, an altered state of reality, into which the audience steps for a brief few hours to emerge on the other side, safe, if not changed in some small way for the lessons learned along the way.

The rules I learned during that summers in the stock theater and during that summer on the Vineyard have stayed with me these past 60 years. My life has revolved around making magic happen, not necessarily as a performer but as the producer, the stage manager, the writer, and that guy behind the curtain in The Wizard of Oz. The rules are: “Don’t let the audience see the wires, and don’t let them see you sweat.” They do not need to know how we do what we do, how we create the magic, or how hard it is to do it; they just want to experience the magic of visiting another reality for a time. If there is a lesson to be learned from the experience, so much the better; if not, then it’s been a pleasant voyage, a time out from their own lives.

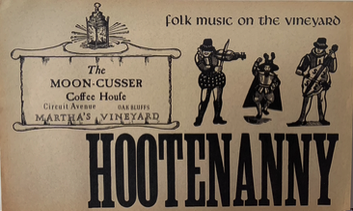

The Hootenanny

The old supermarket on Circuit Avenue could seat perhaps 125 people legally, but on Monday afternoons we removed the tables and chairs into the back alley to make room for the Hootenanny—today it’s called “Open Mike Night.” People sat on the floor, stood along the walls, listed outside on the street, the music pouring out the front door. We could cram in over 200 just for the night.

By 8 p.m., there was a line outside waiting for us to open. We packed the place. There was standing room only. It was so crowded that Philip, standing at the cash register and lighting panel, could not see the stage. He controlled the lights by looking up at the ceiling. There were solo performers, duos, trios, and bands, each with their own entourage, crowding in. A large, industrial fan in the rear of the club sucked out the hot, smoky air into the street adjacent to the post office. It wasn’t air conditioning, but the breeze did have a cooling effect on hot August nights.

Islanders and those from the mainland had access to the stage for a few moments of fame or embarrassment. This is where James Taylor began performing, at age 15. On Sunday evenings, local singer Dave Gude performed along with the Simonn Sisters, Carey and Lucy. They stood there in the spot light, in matching delicate white dresses, each with a guitar, singing “Winking, Blinking and Nod . . . .” On Tuesday evening, the week’s featured acts began a five-night run, usually two acts, a solo and a group. Tom Rush and Jeff Muldour were regulars. The list of acts that summer included some of folk music’s most ingenious singer-songwriters and performers. I got to know and hang with Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Ian and Sylvia, and The Country Gentlemen, Bonnie Dobson. Jean Redpath, who had just arrived fresh from her first US appearance at the Newport Folk Festival. She was having such a good time on the Vineyard that she cancelled her other engagements and spent the rest of the summer with us. She and Eddy Adcock, the banjo player with the Country Gentlemen, teased each other continually. One evening, when everyone wanted to head to the Folk House, Eddy wanted to go drinking at Munrrows, a bar across from the Cusser. Jean simply picked up Eddy, threw him over her shoulder, and carried him down Circuit Avenue.

This was a seven-night-a-week job, but the work was not really work. We loved what we were doing and what we were involved in. There were no days off; besides, what would one do if they had a day off? Where would you go that was better than being where you were?

The Scene

There were late-night beach parties with bond fires, beer, and music. There was romance and sex. “Grass” was around, but not that obvious. Philip and I were both straight and set the tone for the place by saying that drugs were not welcome. The Folk House became a magnet for the more serious musicians on the Island, those who wanted to learn from the visiting musicians. No one woke up at the house until after noon. A bunch of us would drive to South Beach to body surf in the waves. “The Club,” as we called it, opened at 8 p.m. The first act went on at 9-ish, and we wound up just before 1 AM. The place became so well known that the ASCAP office in New York City sent an executive to check us out, with dreams of handing us a fine for performing live music without an ASCAP license.

"We don’t play copyrighted music here,” I explained. “We don’t play Broadway tunes or jazz; we play old folk music, you know, songs that are part of the public domain. Songs from colonial times and English ballads.” He still wanted to listen.

I told my performers that evening to make sure they didn’t sing anything ASCAP could claim was under copyright. The ASCAP chap stayed for the first set, waved goodbye, and left. We never heard from them again. But we did hear from lots of other people. Charley Close, a New York City musician’s agent, showed up mid-summer and hung out for the rest of that first season. He eventually bought out Fritz, one of my backers, and became half owner of the place. Charley represented some of the acts I’d booked and was interested in what the Moon ‘Cusser was becoming. The second summer, Charley brought in Don MacClean as an artist-in-residence. He brought in the actor Alan Arkin who was also a folk singer.

Getting the Word Around

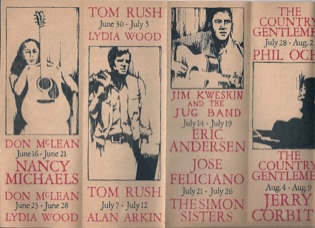

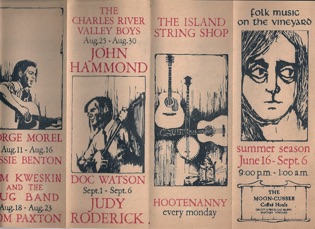

On Thursdays, Philip and I would drive around the Island in his yellow Jeep, putting up posters for next week’s acts. These posters were our major marketing tool, and they became collectors items. For many years, after that first summer, Philip and I used the backs of left-over posters to write letters to each other.

The posters were hand-drawn by a RISD art student using promotional photos I supplied. He turned the images into what looked like old wood cuts. They were printed on 8.5 by 14, recycled rag paper, to make them look old. We stapled them to utility poles, bulletin boards, and the side of Pool’s Fish Market in Menemsha.

"Sure, you can put up your poster; just see you remove the staples,” said Everett Poole. Years later, when Philip stopped into Pooles, he asked if Mr. Pool was serious about removing the stapes.

"Of course I was serious. You leave those staples in cedar shingles, and they rust and split the wood.”

Philip and I got to see a lot of the Vineyard that summer, and I got to hear a lot about growing up in the privileged classes, attending private school, Princeton, and his exploits with girls.

What Carley Simon had to say

From a July 2011 article in The Vineyard Gazette:

"It was thrilling. It was absolutely thrilling. It was the biggest thing that had ever happened to me,” said Ms. Simon, who turned 18 that summer. “It made me inspired to do so much. It obviously had a profound effect on me because I somehow saw it in my mind that I would be singing with a man and that it would be very Vineyard-based, and when you picture something, when you visualize something, it very often comes to be. And so I felt it very much when I met James Taylor. It was like Jessie [Benton] and David [Gude], and as it turned out, Davie had taught James some guitar chords too, just in the way he taught Lucy and me.”

In that same article, Philip Metcalf wrote from his Santa Fe home, “What sort of made it special? I think that one of the things was just that everyone had so much fun,” said Mr. Metcalf. “Because this was sort of an innocent age, there was nothing like it on the Vineyard when it opened; there was no other comparable facility that was offering good live music, a good cup of coffee, or good pastries. The pastries were all handmade by a woman who lived in Washington Park. We’d go up and say, We need two apple pies and a cherry pie, and she would make them, and we’d pick them up on our way to the club each evening.

The Moon ‘Cusser’s Impact

The Moon ‘Cusser had an impact on the Island, on music, and on the lives and careers of people who were here that first summer of 1963. Philip Metcalf and I were close all those years later. Aftrer graduation from Princeton he followed a career in finance in New York, then retired to Santa Fe and passed away in the fall of 2019.

A young kid who hung around the club the second summer, Chuck Kruger, went on to a successful career as a touring musician and concert producer, than as a member of the Maine House of Representatives. Don Maclean (“Miss American Pie) was an “artist in residence” the second summer. Don went on to an illustrious career as a singer-songwriter. He now lives near me here in Camden, Maine. We all know what happened to James and Livingston Taylor, and, of course, Carley Simon. Folk music changed that summer—drugs became more prevalent; politics and the Vietnam War took the music away from its roots, making it more of an advocacy tool for social change. Things changed when Bob Dylan went electric and Judy Collins used strings in the background on her albums. George Papadupalo, the owner of the Unicorn, learned of the Moon Cussser’s success and set up a competing venue that second summer, just down the street in Oak Bluffs. There wasn’t enough audience on the island for two clubs and both failed to open the following summer.

The scene changed, as did the people and the music. But nothing stays the same except our memories, which just keep getting better, if less sharp.

Like Brigadoon, it was a magical summer—9 weeks of music, friendships, romance, and growing up on The Summer Island—it sure would make a hellva movie!

After That Summer

I closed up the Moon Cusser that September and returned to Boston. With another backer, I worked on the launch of Shy’s Rebellion, a larger folk music coffee house adjacent to the Boston University campus in Kinmore Square. It never did open. The draft was after me, as I’d dropped out of college, so I joined the Naval Reserve. In 1967 I was in Vietnam as a US Navy Photojournalist with a Seabee construction battalion. My memoir of that time was released by McFarland Publishing in 2019: Seabee 71 in Chu Lai. (www.seabee71.com).

When I was released from the Navy in the fall of 1967, I went to work as a newspaper editor in Vermont, then a ski magazine editor. In 1973, I launched the Maine Photographic Workshops, a summer school for photographers, journalists, filmmakers, directors, and writers. It was very much in the path of the Moon Cusser. I got to invite the world’s most respected visual artists to spend a week with me in a delightful setting on the Coast of Maine. And, they came, together with hundreds of students eager to learn from. the masters. Over the 35 years I was the school's director and owner, I built the place into a college, and an international center for creative media professionals. Today, it is known as MaineMedia.edu.

kThese days, from my home in Camden, Maine, I write magazine stories about boats, sailing, and The Caribbean while at work on a series of memoirs